“When you go after honey with a balloon, the great thing is to not let the bees know you’re coming.” — Winnie-the-Pooh

Technically, the properties I’m presenting in this “2024” edition of the “Notable Genre Anniversaries” should/could have been done in 2019, since I go in 5 year increments. But, I somehow missed them back then. Another thing: I was going to cover the Jaws franchise this time around, since the novel originally came out in 1974. But, then I realized that I already covered it in 2020 in celebration of the 1975 film. Oops.

In any case, I have four more anniversaries to celebrate this year. However, rather than “kill myself” trying to get all four done this week for a single post, I decided to split them into two posts of two each. Here we go for Part 1…

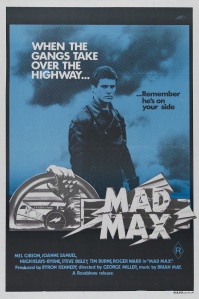

“Mad” Max Rockatansky (1979; 1980 in U.S.): 45 years

On the off chance you’re unfamiliar with it, Mad Max was a post-apocalyptic, dystopian action film from Australia starring Mel Gibson. Society is breaking down in future Australia, gangs are gaining more power and territory, things are generally going down the tubes. Gibson’s ‘Max’ is the top pursuit man of the underfunded Main Force Patrol (MFP) — one of the last remaining law enforcement agencies. When his family is killed by a gang, the enraged Max (in his souped up Pursuit Special) becomes the gang’s worst nightmare.

Former physician George Miller teamed with amateur filmmaker Byron Kennedy to develop an outline for their story concept. Then they added first-time screenwriter James McCausland to the team, and he worked mostly on the dialogue. In addition to contributing personal funds, they earned money for production by circulating a 40-page presentation. Young, American-born Mel Gibson impressed Miller and casting director Mitch Matthews in his audition, and he was signed for the lead role. Most of the biker gang extras were members of actual Australian outlaw motorcycle clubs, and they had to ride their own motorcycles on camera, as well as when commuting to and from shooting locations.

Production had a lot of issues (many due to casting, budget, and time constraints), and it involved a lot of “guerrilla filmmaking”, which then led to “guerrilla editing” of both picture and sound in post-production. On a positive note, Mad Max has the distinction of being one of the first Australian films to be shot with a widescreen anamorphic lens. The film would go on to win Australian Film Institute awards for Best Editing, Best Original Music Score (by composer Brian May (not the guy from Queen)), and Best Sound, along with a Special Award for Stunt Work. There were four additional AFI nominations, and the film won the Special Jury Award at the Avoriaz Fantastic Film Festival.

Critical reception of the film was generally negative, due primarily to the violence and dark tone, though Miller got a nod from Variety. On the other hand,

“Mad Max grossed A$5,355,490 at the box office in Australia and over US$100 million worldwide. Given its small production budget, it was the most profitable film ever made at the time and held the Guinness World Record for the highest box-office-to-budget ratio of any motion picture until the release of The Blair Witch Project (1999)…. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 91% approval rating based on 64 reviews, with an average score of 7.8/10; the site’s ‘critics consensus’ reads: ‘Staging the improbable car stunts and crashes to perfection, director George Miller succeeds completely in bringing the violent, post-apocalyptic world of Mad Max to visceral life.’ The film has been included in ‘best 1,000 films of all time’ lists from The New York Times and The Guardian.”

There were two live-action sequels (1982, 1985) with Mel Gibson, then a new film in 2015 (starring Tom Hardy as ‘Max’), the last one winning six out of ten Academy Award nominations. Miller directed or co-directed all four films. A spinoff prequel is on its way for 2024, and possible additional sequels are in development. The franchise’s influence in popular culture is evidenced in other films and TV series, various music genres (from pop to metal) and music videos, animated TV series episodes, video games, novels, comic books, manga, professional wrestling, etc.

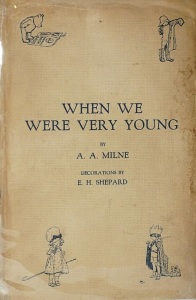

Winnie-the-Pooh (1924): 100 years

Once upon a time, there was a friendly, kindhearted, but not-so-bright, Silly Ol’ Bear that lived in the Hundred Acre Wood with his friends Piglet, Kanga, Eeyore, Tigger, et al. They were often visited by a young boy named Christopher Robin, who joined them on adventures, picnics, games, and musings about life, love, and friendship. They all sprang from the minds of English author A.A. Milne and illustrator E.H. Shepard.

The bear was originally named “Edward Bear” when he first appeared in Milne’s poem, “Teddy Bear”, in the Feb. 13, 1924, edition of Punch. The name ‘Edward’ came from a teddy bear Milne had given his son, the real Christopher Robin, for his first birthday in 1921. By the time the poem was republished in Milne’s book of children’s verse, When We Were Very Young (Nov. 6, 1924), the child had re-named the toy. ‘Winnie’ was the name of a brown bear they saw at the London Zoo, while ‘Pooh’ was what Christopher Robin Milne called a swan that he fed every morning. Milne’s popular character first appeared publicly as ‘Winnie-the-Pooh’ (though the hyphens would eventually be removed) in a Christmas story commissioned and published by the London Evening News newspaper (Dec. 24, 2025).

Winnie-the-Pooh’s design came from ‘Growler’, the teddy bear of Shepard’s son Graham, which was more cuddly than young Milne’s “gruff-looking” teddy bear. Many of the other animal characters were based on Christopher Robin Milne’s other stuffed toys. ‘Hundred Acre Wood’ was based on the very real Five Hundred Acre Wood in Ashdown Forest in East Sussex, a few miles from the Milne country home. Many other locations in the stories — from a particular clump of trees to a prominent hilltop or a footbridge — are associated with very real places in and around the forest.

The first collection of Pooh stories appeared in the book Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), published by Methuen in England, by E.P. Dutton in the U.S., and by McClelland & Stewart in Canada. It was “an immediate critical and commercial success.” Milne and Shepard put out a successful sequel, The House at Pooh Corner (which introduced the ‘Tigger’ character) in 1928.

Creator/producer/publisher Stephen Slesinger bought US and Canadian merchandising, television, recording, and other trade rights to the Winnie-the-Pooh works from Milne in January 1930 “for a $1,000 advance and 66% of Slesinger’s income. By November 1931, Pooh was a $50 million-a-year business. Slesinger marketed Pooh and his friends for more than 30 years, creating the first Pooh doll, record, board game, puzzle, US radio broadcast (on NBC), animation, and motion picture.” Pooh and friends first appeared in color in 1932 on an RCA Victor picture record. That was, of course, the debut of Pooh’s trademark red shirt, as well.

When Slesinger died in 1953, his wife Shirley continued the business. In 1961, both Slesinger’s widow and Milne’s widow, Daphne, licensed the respective rights they controlled to Walt Disney Productions. Disney retained exclusive rights to the property until Jan. 2022, when the U.S. copyright expired and it went into the public domain. An independent filmmaker quickly capitalized on this by putting out a horror film titled Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey (2023). (The UK copyright will expire in Jan. 2027.)

Between Slesinger and Disney (who have had legal disputes, btw), the Pooh franchise has continued to release live-action movies and featurettes, animated films, games, radio dramas, musical releases, TV series, musical shorts, unofficial sequel books, related books, stage productions,

and, of course, stuffed toys of Pooh and the other characters. A few of Milne’s stories were even adapted in the Soviet Union. Various of the Pooh productions have been translated into various languages, including Russian (of course), Polish, Hungarian, Latin, etc. Here is a Wikipedia quote regarding Pooh’s cultural legacy:

“Maev Kennedy of The Guardian called Winnie-the-Pooh ‘the most famous bear in literary history’. One of the best-known characters in British children’s literature, a 2011 poll saw the bear voted onto the list of top 100 ‘icons of England’. In 2003 the first Pooh story was ranked number 7 on the BBC’s The Big Read poll. Forbes magazine ranked Pooh the most valuable fictional character in 2002, with merchandising products alone generating more than $5.9 billion that year. In 2005, Pooh generated $6 billion, a figure surpassed by only Mickey Mouse. In 2006, Pooh received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, marking the 80th birthday of Milne’s creation. In 2010, E.H. Shepard’s original illustrations of Winnie the Pooh (and other Pooh characters) featured on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail.”

Who would’ve thought that this hunny-lovin’, Bear of Very Little Brain would be so popular a century later?

Stay tuned for Part 2 in the weeks ahead (and before I go on vacation in June)…